Whan that aprill with his shoures soote

The droghte of march hath perced to the roote,

And bathed every veyne in swich licour

Of which vertu engendred is the flour;

— Canterbury Tales, General Prologue, Chaucer1

English has come a long way since the late 1300s and Geoffrey Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, written in the vernacular of the time: Middle English (ME). As you may be able to tell, it’s barely intelligible on paper, much less so in spoken form.

Fast-forward about 200 years, to the Early Modern English (EMnE) period circa 1600. William Shakespeare’s Henry V gets us a little closer to the modern day.

O for a Muse of fire, that would ascend

The brightest heaven of invention,

A kingdom for a stage, princes to act

And monarchs to behold the swelling scene!

Then should the warlike Harry, like himself,

Assume the port of Mars; and at his heels,

Leash’d in like hounds, should famine, sword and fire

Crouch for employment.

— Henry V, Act I Prologue, William Shakespeare2

And it’s pretty easy to understand the pronunciation. (Jump to 2:51)

At this point, we can understand all the words on the page and stage, but understanding the sentence as a whole can be a bit of a pain. However, this was the way that we think people spoke back then, and from looking at the writing, it’s definitely the way they wrote.

“How came it here?”

As fantasy authors began writing books set in the ME-EMnE periods, they used language drawn from some of these time periods3. Sometimes, they took elements from several different periods that wouldn’t have coexisted, proper research be damned. Sometimes, they’d lay on the Medieval-souding dialect so thick that the ridiculousness of it could distract the reader from the book. Kate Cox of Kotaku complains of an RPG character saying, “How came it here?” and recounts how that line was the last straw:

Not every hapless hero, farm boy, knight, warrior, or even mage needs to declaim every portentous word from on high. It’s all right to stay simple. English is a fantastic language; I wish more characters in the games I play would learn simply to speak it, rather than to orate in it.4

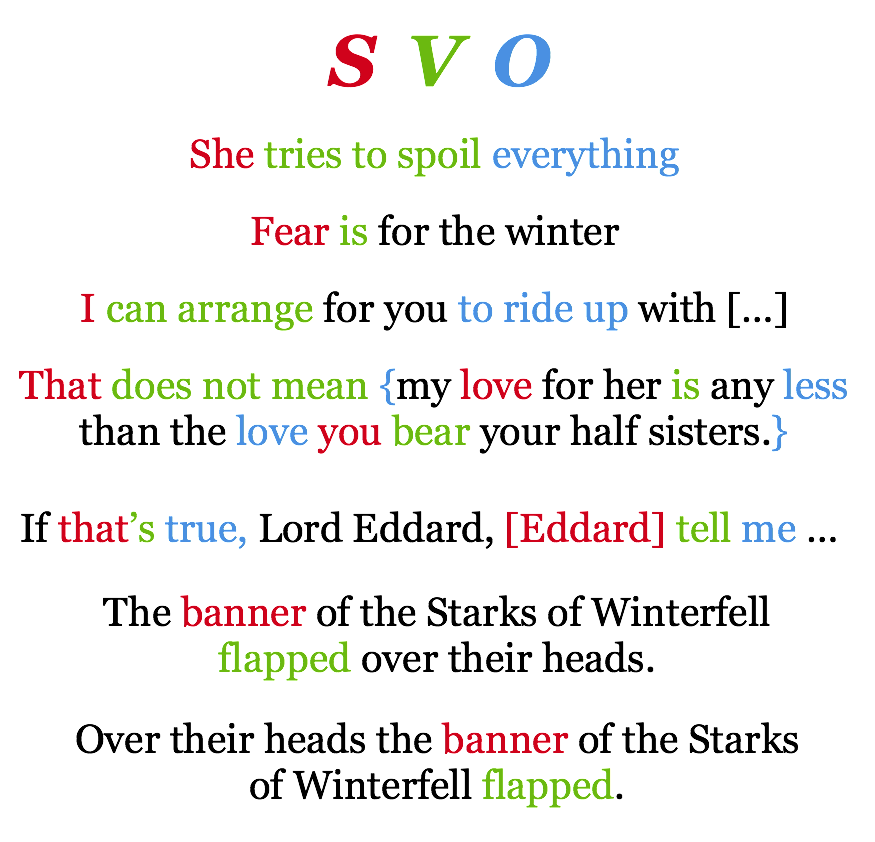

Thankfully, I feel like fantasy authors that want to be taken seriously have listened to voices like Cox’s and toned down the thee-thou-thine factor. I noticed this while reading George R. R. Martin’s A Game of Thrones this summer. All of the characters speak in a mostly normal, Present Day English (PDE) dialect. Here’s a representative sampling of dialogue I culled by opening the book to random pages and copying down something a character said.

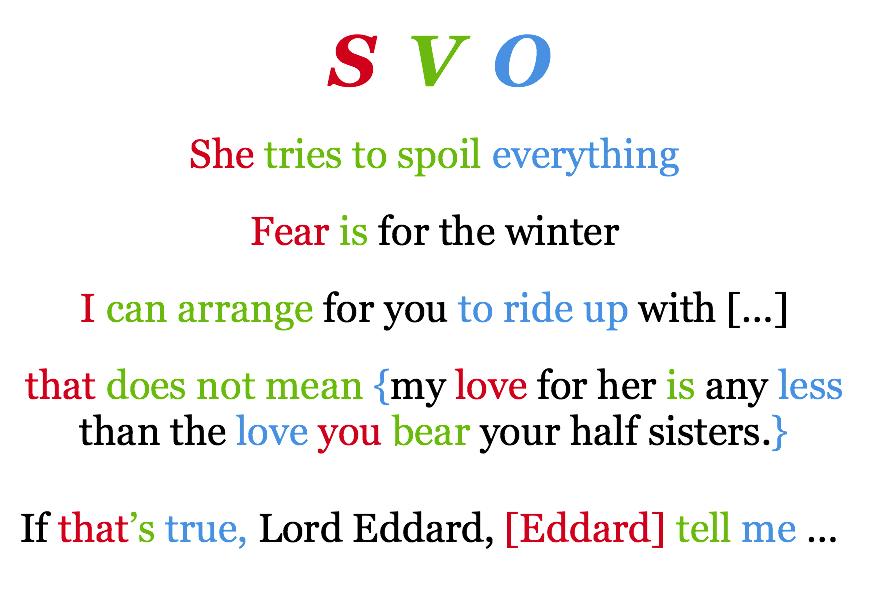

Representative samples of normal-ish dialogue

“Nor will I. Leave it be, Robert, for the love you say you bear me. I dishonored myself and I dishonored Catelyn, in the sight of gods and men.” (110-11)

“The watch commander tells me I must walk, to keep my blood from freeezing, but he never said how fast.” (212)

“Fear is for the winter, my little lord, when the snows fall a hundred feet deep and the ice wind comes howling out of the north.” (240)

“If you prefer, my lord of Lannister, I can arrange for you to ride up with the bread and beer and apples.” (368)

“She tries to spoil everything, Father, she can’t stand for anything to be beautiful or nice or splendid.” (487)

“If that’s true, Lord Eddard, tell me … why is it always the innocents who suffer most, when you high lords play your game of thrones?” (636)

“Truth be told, I can hardly stand to be around the wretched woman, but that does not mean my love for her is any less than the love you bear your half sisters.” (783)

From time to time, characters slip into a more formal register. I noticed that this happens more in Lannister speech. I’d attribute this to the Lannisters being the ruling family and using a more formal register to assert their dominance. Daenerys, Drogo, and their supporting characters also use a more formal register, I’d say because some of the characters aren’t speaking in their first language. Daenerys and Joffrey in particular seem to use a formal register more than others. Because both of them are young future members of the ruling class, they might be adopting a sociolect with higher prestige to compensate for their youth, to show that they have what it takes fit in with their elders.

Occasional formal elements in dialogue

“The rest shall wait here until I send for you.” (608)

“Take my betrothed back to the castle, and see that no harm befalls her.” (301)

“I shall make you a cloak of its skin, moon of my life.” (593)

“He should look a king in the sacred city. Doreah, run and find him and invite him to sup with me.” (392)

When I came across this line:

“You will attend me in court this afternoon,” Joffrey said. “See that you bathe and dress as befits my betrothed.” (743)

I started looking up the prefix be- in the OED, and found a whole host of funny-sounding obsolete words. It quickly developed into its own post instead of just a segment of this post. Check it out if you’re up for a side quest.

From dialogue to narration

As I established earlier, the dialogue contributes just a little to the quasi-Medieval setting. The more I read, however, I began picking up on small structures not in the things that the characters said, but in the things that nobody said. George R. R. Martin actually used sentence structure and certain grammatical features to lend a feeling of old-timeyness to his writing when describing things.

Martin sprinkled his writing with the typical disused words evocative of olden times, your fortnights and your name days and some others we might not hear nowadays [emphasis mine]:

Riverrun sat athwart the Lannister supply lines. (793)

He had taken off Father’s face, Bran thought, and donned the face of Lord Stark of Winterfell. (14)

Ned broke his fast with his daughters and Septa Mordane. (523)

Bronn came trotting out of the mists, already armored and ahorse, wearing his battered halfhelm. (682)

These are examples of simple changes in vocabulary choice to imitate a language style period, but Martin goes even further with his use of different grammatical constructs found only in earlier versions of English. The rest of this post consists of several examples I found while reading.

Be as an auxiliary for the present perfect

The English present perfect is formed from an auxiliary verb and “the [past participle] of another verb, to form a series of compound or ‘perfect’ tenses of the latter, expressing action already finished at the time indicated”.5 Originally some verbs took forms of have as their auxiliary, while

[…] verbs of motion and position long retained the earlier use of the auxiliary be; and he is gone is still used to express resulting state, while he has gone expresses action.

– have, II

This distinction continued for a time, but the be auxiliary is

Now largely replaced by have following the pattern of transitive verbs.

— be, IV, 16, b6

So nowadays, we’d use have as the auxiliary in a situation like this:

Damn her, he thought, why is the woman not fled? I have given her chance after chance … (523)

Granted, it’s debatable whether Ned is wondering about the action of fleeing or the condition of having fled. Still PDE would say something like “why has the woman not fled?”.

Need as an auxiliary expressing necessity

This next one’s a double-header!

Ned was not near as confident of Robert as he pretended, but there was no reason Cersei need know that. (481)

Unfortunately I can’t find anything that proscribes “not near as” in favor of “not nearly as” (other than this worksheet from a random website), but “not near as” just feels like the more outmoded version of the two.

However, later in that same sentence, we find another interesting artifact. The most commonly used modal auxiliaries are can, could, shall, should, may, might, must, used to, and ought to. They take the root form of the verb, which remains unchanged relative to person and number: they can go, she must stay, I could eat. Need used to behave similarly, but according to the OED it doesn’t anymore.

(d) With bare infinitive. Obsolete.7

- 1865: Needs not say how lovely are the summer evenings.

– need, I, 1, a.

V2 word order

In the ME period, English word order diverged from that of its Germanic sister languages. PDE is primarily a Subject-Verb-Object (SVO) language, meaning that the elements of the sentence have to come in a certain order. Certain situations, like questions, commands, and subordinate clauses, don’t exhibit SVO. It is the best choice in main clauses, however. Here are a few examples from the dialogue above:

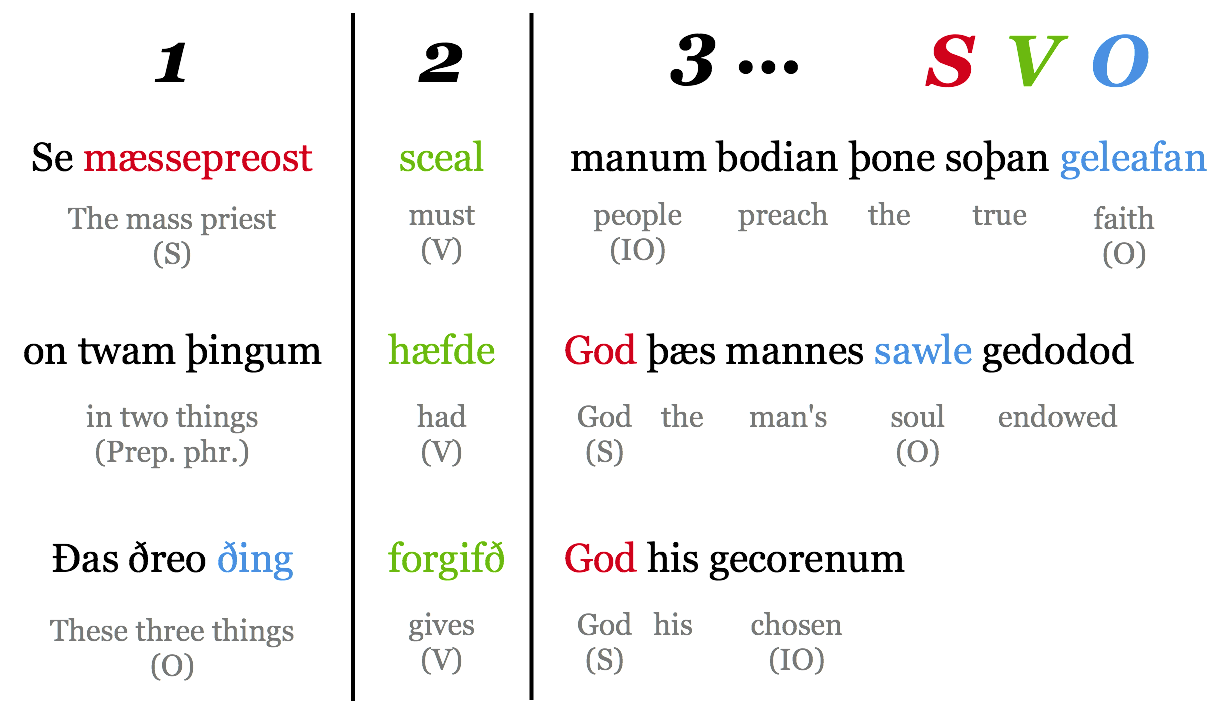

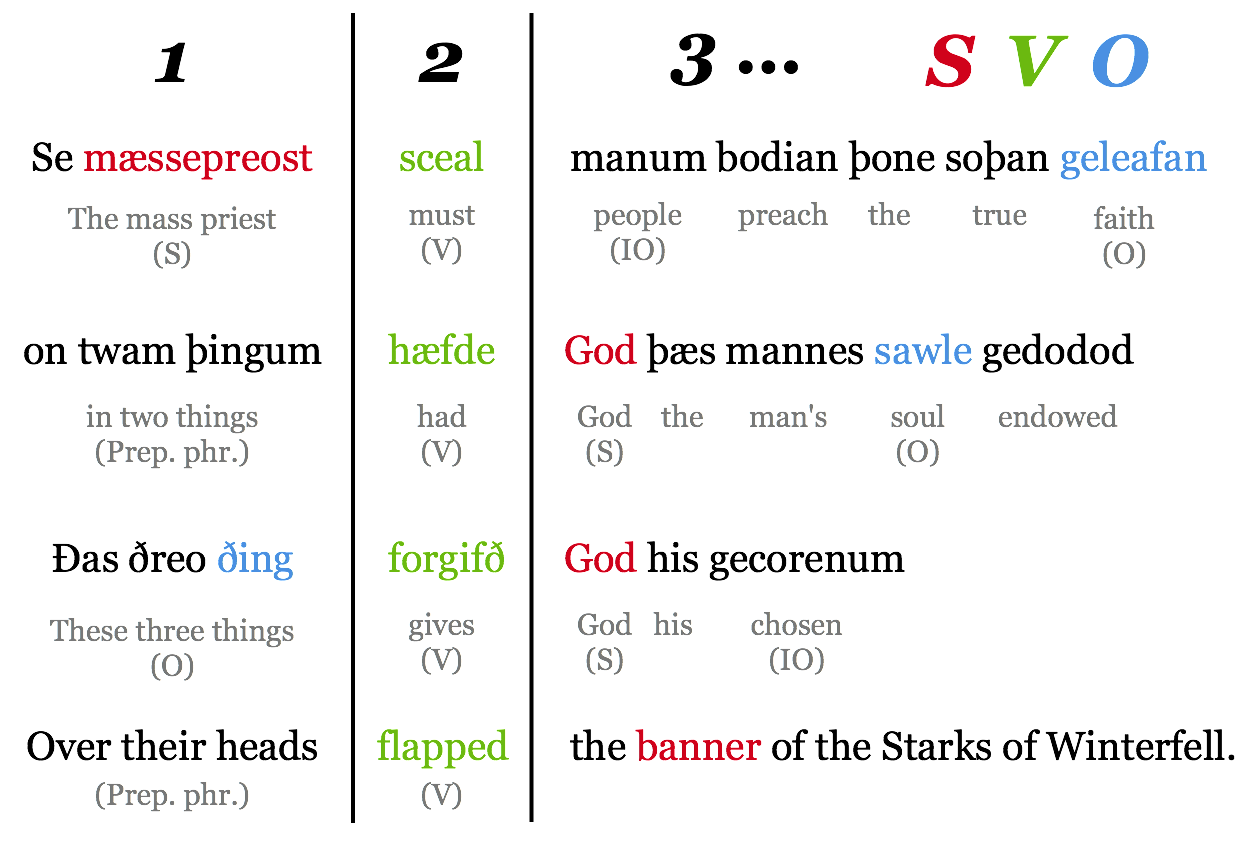

All other Germanic languages exhibit what’s called a Verb-Second (V2) word order. In this word order, the verb (or auxiliary verb, if present) must be the second thing in the sentence. If something else needs to come in front, like an adverbial or a negative word, the subject must skip past the verb and take a place later in the sentence. English was a V2 language, but only until the ME period. OE is fully V2:

"With two things God had endowed man's soul."

"These three things God gives to his chosen."[^8]

By usual standards, our sample OE sentences exhibit the usual SVO, then VSO, then OVS: the word order is all over the place! But the verb or auxiliary is always the second thing in the sentence, so it’s permissible in this language.

A few remnants of V2 word order in PDE can be found in phrases like “Never have I ever (verb),” “Here lies (name)”, “Thirty days hath September…”, and “Under no circumstances will I agree.”8.

Now check out this line from A Game of Thrones [emphasis mine]:

Over their heads flapped the banner of the Starks of Winterfell: a grey direwolf racing across an ice-white field. (14)

That line fits in perfectly with the OE sentences written in V2 word order. Martin could have chosen to structure it using an SVO order:

But he didn’t. He deliberately chose a word order characteristic of Old English instead of the modern standard. Fowler would call this instance of displacing the subject Balance Inversion, and he had some choice words to say about it:

Inversion and variation of the uncalled-for kinds are like stiletto heels—ugly things resorted to in the false belief that artificiality is more beautiful than nature. (296)9

Luckily for us, he’s been dead for 80 years. I think the unconventional word order is a subtle yet effective way to change the reader’s perception without him or her realizing it.

Unmarked measure words in the plural

Another feature from OE that has largely vanished is the practice of leaving measure words unmarked. This usage survives in PDE when a measurement is used as an adjective directly preceding a noun. Examples include Three Mile Island (not *Three Miles Island), fifty-gallon hat (not *fifty-gallons hat), and a sixty-mile-an-hour wind (not *a sixty-miles-an-hour wind). It even happens in measurements that aren’t names: we’d say we went on a five-mile run, ate a two-pound steak, and then took a three-hour nap.

Of course, when uncoupled from their nouns, these measure words revert to the regular plural formation: your run was five miles long, the steak weighed two pounds, and your nap lasted three hours. So if Tyrion had said he felt like a “thousand-stone man,” that would fall under acceptable PDE usage. However, we see this instead:

He needed help to mount; he felt as though he weighed a thousand stone. (683)

The unmarked plural measure word appears outside its typical confinement to the noun it modifies. Martin’s choice of a disused unit of measurement is a bonus anachronism.

Leftovers

I found a couple sentences that had non-standard grammar, but I’m not sure where to find the required grammatical points.

Tyrion Lannister chalked up one more debt owed the Starks. (324)

Replacing the omitted words gives us:

Tyrion Lannister chalked up one more debt [that he] owed [to] the Starks.

or possibly an impersonal passive formation:

Tyrion Lannister chalked up one more debt [that was] owed [to] the Starks [by (whoever ends up paying the debt)].

I think omission of the relative pronoun, the subject pronoun/auxiliary, and the preposition introducing the indirect object just puts me off a little, but I don’t know if it obeys any disused grammatical rules.

Here’s another one:

Catelyn Stark shared all their doubts, but she had only to glance at Ser Stevron to see that he was not pleased by what he was hearing. (644)

In a “have to [verb]” formation, PDE typically doesn’t allow anything to come between the components: “She only had to glance.” Maybe that rule only came about recently. In any case, it sent up a red flag for not following typical rules, so I thought I’d include it.

In conclusion

Thanks for reading! I hope you learned something interesting about English today. I’m going to return the book to my friend Spencer, who has so graciously lent it to me, and keep plugging with the next book. Hopefully I’ll notice something else cool in that book and I can add it to the list! See you later!

— Dan

P.S. In case you were wondering, “gamen cynestōla” is Old English for “a game of thrones,” according to Phil Barthram’s Old English Translator engine.10

Cover image credit: Game of Thrones Wiki

-

Any Knights-of-the-Round-Table-y fantasy book you read in middle school. ↩

-

The Trouble With Most High Fantasy Dialogue Is That It’s Terrible, Kate Cox on Kotaku ↩

-

The syntax of natural language: An online introduction using the Trees program, by Beatrice Santorini and Anthony Kroch ↩

-

Fowler’s Modern English Usage, 2nd edition. ↩

-

Old English Translator: game, throne. OE didn’t have indefinite articles that worked like ours, and “cynestōla” is in the genitive case, so it already contains the meaning of the word “of.” ↩